Moving Toward Transformational Impact

Standard 1 requires a school seeking accreditation to identify a strategic intention or area of focus around societal impact. The school also needs to show that it has a clear strategy for embedding that focus area into its curriculum (as outlined in Standard 4), its scholarship (Standard 8), and its other engagement activities (Standard 9). These three activities are joined not by an or, but an and.

In other words, a school cannot simply report a laundry list of good things it is doing and spin those activities into a story. It needs to pick a strategy, build activities around it, and demonstrate the results of its efforts. It’s nice to tell compelling stories, but at this stage of the game, we really want to see that a school has set clear goals to achieve objective, legitimate, and meaningful impact.

Choosing a Framework

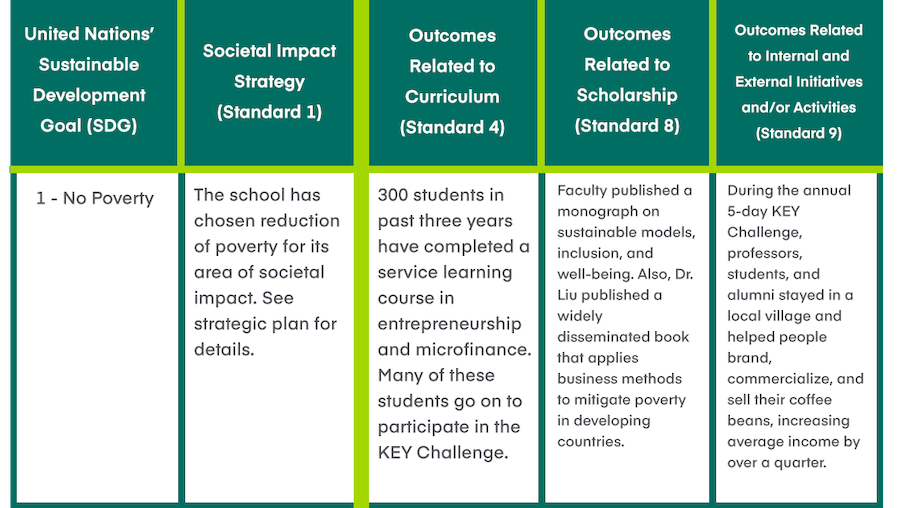

To be able to demonstrate impact, school administrators first must identify a strategic area of focus. In our July 1, 2021, update to the accreditation standards, we include a new tool, Table 9-1, designed to help schools present their societal impact themes along standards 1, 4, 8, and 9. The table is formatted so that schools list the framework they have selected down the left side, with the applicable standards across the top.

The sample table provided in the accreditation standards is built around the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework, which identifies 17 categories of societal problems that need to be addressed to “achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.” In 2015, the SDGs were adopted by all member states of the United Nations. AACSB chose the SDG model because of its comprehensiveness and growing acceptance in the corporate world. In fact, in 2020, S&P Global conducted a survey of 250 companies in the S&P 500 and found that 82 percent of respondents say they have reported on their progress toward the SDGs.

However, schools can use any framework they desire, such as the Global Reporting Initiative, Morgan Stanley Capital International’s ESG (environmental, social, and governance) framework, and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board’s ESG framework. A school also can use a unique framework it has developed.

While there are many areas of societal need that a school could address, its administrators should choose only a few—perhaps only one—that they want to focus on, so they can concentrate their efforts and resources. Once they have chosen an area of focus, administrators should discuss it with the entire faculty, who can then supply information about how they are incorporating the focus area into their activities. Not all professors need to be engaged in every activity, but the faculty as a whole should demonstrate an energy and shared vision around the focus area.

Below is an example of a completed Table 9-1 as filled out by the University of Pirsig’s School of Business, a fictitious institution. This example, which appears in the 2020 Interpretive Guidance for AACSB Business Accreditation, shows that the school has chosen to create societal impact by focusing on SDG 1, eliminating poverty. It also shows how the school has addressed that goal in all the areas of the standards that relate to societal impact.

A sample Table 9-1 from the 2020 Interpretive Guidance for AACSB Business Accreditation

Demonstrating Impact

As the table makes clear, teaching, research, and engagement activities all lead to outputs. However, and this is important, outputs in and of themselves are not sufficient to satisfy AACSB accreditation requirements. In many ways, counting outputs is similar to counting peer reviewed articles—in the past, our industry has placed far too much emphasis on simply checking boxes to come up with impressive numbers. If we count just the number of journal publications without connecting those activities to impact, we will have a system that encourages meaningless churning instead of a system that that fosters outcomes with demonstrable impact.

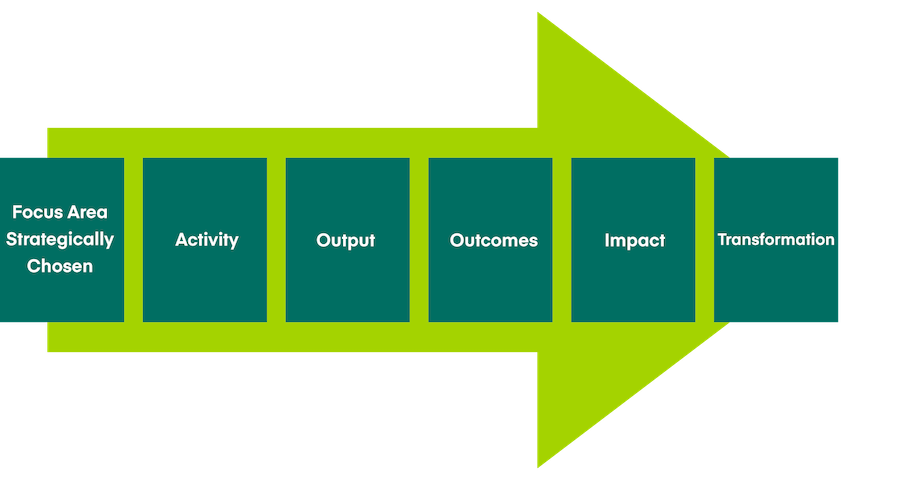

Instead, we should expect a school’s focused activities to result in specific outputs that create measurable outcomes, which in turn lead to meaningful change and demonstrable impact. Over time and through cumulative years of effort, meaningful change can lead to the transformation of an ecosystem. (See graphic below.) It might take years before true transformation is evident—in fact, the authors of “A New Future for Research” note that it might be a decade before business schools fully transition into focusing on impact-based scholarship. But that’s all the more reason for schools to start the journey now.

Table 9-1 will provide some information about a school’s planned path from activity to transformation. However, since the table is intended to provide a high-level view of the school’s activities and impact, some details will be omitted from the table for the sake of brevity. Therefore, peer review teams will look to a school’s continuous improvement review report for more specific information about how a school’s outputs are directly connected to outcomes and impact.

Let’s look again at our sample Table 9-1 for the University of Pirsig’s School of Business and supplement it with information the peer review team might have found in the continuous review report.

In its curriculum, the school’s activity was to design and implement a service-learning course in entrepreneurship and microfinance. Its output was 300 students who took the course. The outcome was that many of those students went on to participate in the school’s annual KEY Challenge, in which students teach local villagers how to use the techniques of microfinance and entrepreneurship to start their own small businesses. The villagers who have participated in the challenge have seen a 25 percent increase in annual income, which is the measurable impact of the activity. Over time, if the school participates in the program for several years, the transformation for these villagers could be dramatic.

In its scholarship, the school’s main activity was the research that faculty conducted on improving well-being through financial sustainability. The output was a monograph three professors published about sustainable models, inclusion, and well-being, as well as a book other faculty published about mitigating poverty in developing countries. Because the book and the monograph were widely disseminated, the outcome was that they were cited in both academic articles and the popular press. Both publications had an impact on the institution: The business school enhanced its reputation as a thought leader in the area of poverty, received several invitations to present in other forums on these topics, and saw seven other universities adopt the monograph as part of their financial sustainability curricula. Only time will reveal the ultimate transformation these research efforts achieve.

In the external initiatives and activities section of Table 9-1, administrators chose to highlight the KEY Challenge because it was so central to the school’s goal of reducing poverty. The activity was the KEY Challenge itself, the output was participation by the school community, the outcome was an improved standard of living for villagers, the impact was the 25 percent increase in income, and the transformation will be measured over time.

Never has it been more imperative for business schools to collaborate to improve the world as it faces myriad complex problems. Business schools can be change makers who create real societal transformation.

As this example makes clear, outputs are easily identified, but outcomes require administrators to think about the long-term effects of their activities. What happened? How many people were affected, and to what degree? Students completed a course—so what? A book was published—so what? Administrators must employ deep thinking to move past storytelling and identify outcomes, impact, and transformation.

Making Connections

Although the 2020 accreditation standards have heightened the emphasis on societal impact, schools should not take a scattershot approach to creating impact through long lists of unrelated activities. Instead, they should make strategic choices about what they will support through their curriculum, scholarship, and engagement efforts. Therefore, in the portion of their accreditation reports specifically related to societal impact, schools should resist the temptation to list activities that are not relevant to their chosen areas of focus.

Over time, AACSB plans to help schools connect with others that are working on the same areas of societal impact. Joint efforts will greatly magnify the impact a single school can have.

These are exciting times for management education. Never has it been more imperative for business schools to collaborate to improve the world as it faces myriad complex problems. Business schools can be change makers who create real societal transformation.

As Walter Payton, a running back for the Chicago Bears football team, once said, “We are stronger together than we are alone.” Business schools are in the business of changing lives—but we can only change people’s lives for the better if we work together.