A New Future for Research

Around the world, business and management schools are being asked to justify and make visible the value they bring to society. Policymakers and the public want to know, beyond educating students and practitioners, how do business schools contribute to the greater good through their research? How can they augment those contributions further?

For too long, business and management schools have not had good answers to these questions. However, we offer a road map that our sector might follow to promote engagement, drive greater societal transformation, and demonstrate the value of our scholarship.

The Price of Rigor

Over the past 25 years, knowledge production in our field has matured, resulting in three interrelated outcomes. First, business schools have transformed themselves from teaching-driven institutions into research-driven institutions, where scholars have developed their abilities to conduct rigorous analysis and identify promising practices. Second, business scholars have begun to mimic researchers in the natural science disciplines, causing fields of research to coalesce around a hierarchy of select journals. Finally, schools have developed a system of incentives that puts a heavy emphasis on academics’ publishing productivity.

On the plus side, business and management research has developed more theoretical and methodological rigor and gained credibility within the academy. For a field that, not too long ago, was a domain of practice desperately in need of a theoretical base, this has been an important development. However, this rigor, prized so highly, has also carried a price. Much of our research is written in esoteric language and published in specialized journals rarely read by practitioners.

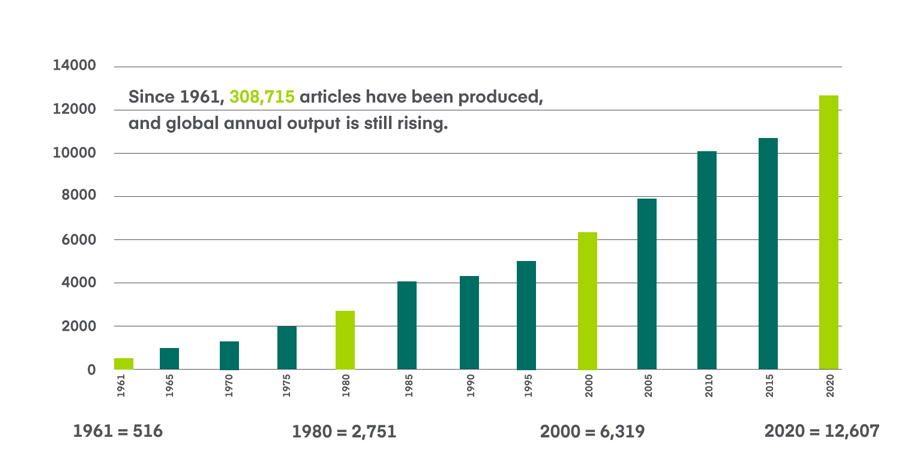

The global article factory. The number of articles published annually in four or four-star journals has escalated over the years. But only 138 out of 1,700 journals are rated as four or four-star in the Chartered Association of Business Schools’ 2021 Academic Journal Guide—representing just the tip of the publishing iceberg. (Source: Scopus)

More fundamentally, competition for publication space is so high, and the set of articles that can be absorbed so limited, that vast amounts of research are published in outlets that hardly anyone, including academics, read. Furthermore, business research often takes so long to be published that the currency of the knowledge is compromised and other players, such as consultancies, capture the agenda.

At the same time, junior faculty are under such pressure to publish quickly that many pursue lower-risk research strategies. More senior faculty should have greater freedom to make more fundamental contributions that may carry higher risks, but often they have not received the training that would enable them to break out of their disciplinary silos. In both cases, the innovation and impact of their research suffer.

How can our institutions justify this system to those who ultimately fund our research, be they students or taxpayers?

‘Blue Sky Research’ Is Not Enough

Of course, we believe theoretical scholarship is a valuable endeavor. It results in the type of “blue sky research” that reveals new ways of seeing the world and provides foundations for further knowledge development. But such research has mostly disciplinary-specific value and addresses narrow, theoretically driven questions. It also tends to favor the “lone researcher” model, supporting individual research at a time when society’s grand challenges require solutions born of diverse, cross-disciplinary perspectives.

In many respects, business scholars are ideally positioned to address such global challenges whose resolution involves multiple stakeholders and requires much more than just new technologies. For example, no one will magically solve the problem of climate change by replacing carbon-based technologies with hydrogen-based technologies. Instead, doing so will involve working with organizations to invent new ways to use energy, travel, and manufacture goods. Likewise, “green plastics” will not solve the problem of plastic pollution in the oceans, unless we help companies reexamine their supply chains, change their packaging, and encourage their customers to adopt different buying habits. It is here that business and management research can make major contributions.

However, narrowly focused single-discipline theoretical research provides an insufficient foundation for precipitating the changes that society needs. Instead, we should aim to live our theories in the real world. If our research is to act as a platform for change, we must move toward a more impact-driven strategy. If we are to contribute solutions that lead to a more sustainable future for all, we must produce those solutions in partnership with our stakeholders.

Putting a Premium on Impact

Fortunately, over the past decade, we have seen a movement to encourage greater responsibility and openness in the broader academic ecosystem. Efforts in this direction include the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), established in 2007; the European Union’s Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Framework, in 2010; and the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), in 2012. The Responsible Research in Business and Management (RRBM) network, which prioritizes research that addresses social problems, and the U.K.’s ongoing Research Excellence Framework, which emphasizes policy and practice impact, were both introduced in 2014.

These worldwide efforts are evidence that policymakers are putting a premium on impact and relevance in their assessments of academic research. Governments are increasingly demanding that business and management schools focus on their civic role. Schools themselves are reexamining their institutional contexts, and the way they define purpose is rapidly changing.

But to ensure that the knowledge they produce will do good for the world, schools of business and management must do far more. They must change their missions, governance, faculty, and knowledge production models for both research and education, as well as embrace more transformative, human-centered knowledge production models. And they must do so in collaboration with other disciplines and key external stakeholders, including policymakers, practitioners, and public groups.

This transition will probably take at least a decade to fully unfold. However, in recent years, we have seen accreditation organizations encourage these developments. Many schools are changing their missions to make their impact as important as their education and research.

A Clear and Shared Vision

Business schools need a shared vision of their research future. At the moment, this vision is still hazy, but it is becoming clearer as research councils, funding bodies, accrediting bodies, and key global stakeholder networks—such as the U.N. Global Compact and the World Economic Forum—actively explore the possibilities.

Whether schools are public or private, full-service or postgraduate, freestanding or embedded in larger universities, they all can fundamentally adopt one of three key models to reposition their research:

The broker model. Under this model, the business school is part of a wider institution and plays the role of co-producer with other disciplines. Its faculty seek to work with the school's partners to generate more impact and value together. The broker model can be effective if a business school’s parent university values it as a research entity in its own right. Unfortunately, parent institutions too often exploit and devalue the knowledge production of business schools to drive investment in STEM-oriented fields considered more “fundamental.”

The relevance model. Here, schools incorporate real-world relevance into the existing core of their research portfolios. Essential to this model are not only rigor and relevance, but also an emphasis on making scholarly research accessible to practitioners. The limitation of this model is that it still emphasizes scholarly publication over the translation of research for practice.

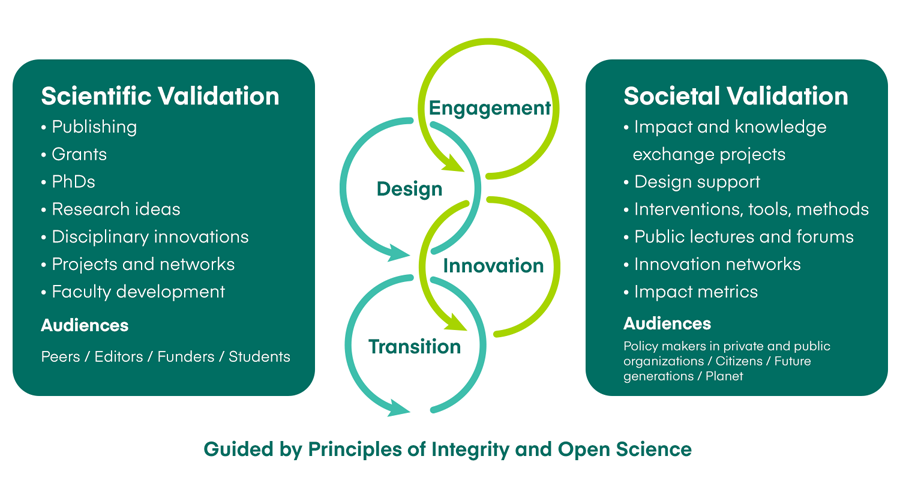

The catalyzing model. This model, which has the notion of co-creation at its core, moves business schools from an emphasis on “linear valorization,” in which schools and faculty are the primary beneficiaries of research, to an emphasis on “dual validation,” which recognizes that business and management research is a social science in which schools co-produce research and solutions with key societal stakeholder groups. (See image below.)

The catalyzing model for research uses dual validation, an approach that emphasizes interactions between science and society.

While there is value in all three models, the catalyzing model holds the greatest promise in the long term. But it also presents the greatest challenges. One of them is the reputational challenge. An approach involving dual validation requires a school to reassess its objectives and standards, as well as reclaim its position in the larger academy as the home to a multidisciplinary social science.

In the end, we must recognize that the real world—with all of its uncontrolled conditions—is our laboratory. Our scientific practices must search out and unravel complexity and interconnectivity. It’s time for us to create a new shared identity in the social sciences, in which we can clearly demonstrate the value of our research and ensure its application for bringing about real-world, positive change.

Where to Start

To make a catalyzing model of research a reality, administrators of business and management schools must embrace change on three fronts:

Leadership and governance. Reimagining research requires visible and inspirational leadership, in the form of new dean or associate dean positions dedicated to promoting engagement and impact. Our schools, the Rotterdam School of Management at Erasmus University in the Netherlands and Lancaster University Management School (LUMS) in the United Kingdom, each employ such an individual to help drive transformation and take the lead in engaging with societal stakeholders.

Those holding these positions cannot operate in isolation. They must be backed by specialist support staff, and they must partner closely with a dean or associate dean for research. In addition, they must have the overt support of the dean and the entire senior leadership team to give their work the internal legitimacy and visibility needed to garner wider institutional support. These components are critical to building an engaged, impactful research culture.

Supporting structures. Most business schools have been organized around disciplinary silos and have tended to focus their investments on individual researchers. But to address grand societal challenges, schools must break down silos and foster interdisciplinary teams of researchers with complementary skills. They must emphasize interdisciplinary work as they secure and allocate funding and engage policymakers.

They can also embrace a catalyzing model through their interdisciplinary research centers. The Erasmus Centre for Data Analytics, with its focus on the transformation of industries and society by data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, is one such example. Another option for business schools is to embed policy think tanks in their institutions. LUMS has done just that with the Work Foundation, a think tank dedicated to improving the quality of working life in the U.K. Through its partnership with the foundation, the school can engage directly in major policy debates around the future of the economy.

Staffing and skills. In the past, business schools’ default position has been to reward researchers for pursuing linear careers based on academic publication to the exclusion of other criteria. To break out of this self-imposed research trap, they need to embrace a different kind of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

In other words, schools need to diversify their faculty by appointing academics who engage with policy and practice as part of their ethos and identities. They need to foster equity by rewarding both those faculty who are strong engagers and communicators and those who publish prolifically. They must provide their faculty with continuous professional development in engagement and impact and offer a wider range of career opportunities and pathways to attract the best talent. Finally, they need to build inclusive teams that bring together academics with differing skills to generate ideas, secure funding, produce academic publications, and translate findings into practice.

The legitimacy challenge that our business and management schools must overcome is also a great opportunity. If their leaders and researchers grasp this opportunity, their knowledge production can make a decisive contribution to addressing the challenges our societies and economies face today.

Mijnhardt is a member of the Responsible Research in Business and Management’s Global Working Board and chair of the United Nation’s PRME subcommittee on impact reporting.