The 10 Smart Skills of the Future

As a business school professor, I find that employers, students, academics, and practitioners all ask me the same questions: “What skills do I need for my future? Should I focus on understanding artificial intelligence, coding, bitcoin, and fintech? Should I also work on communication, negotiation, and employee management?” In other words, they want to know what “soft” skills they should work on and what “hard” skills they should invest in.

But what if the skills of the future are not “soft and hard,” but “smart and sharp”?

The terms “hard and soft skills” were coined in 1972 by the U.S. Army to differentiate the abilities of people who were good at machine operations from those of people who did well supervising others. I think it’s time to update those classifications by choosing words that reflect the roles these skills play in our day-to-day lives. In 2019, I published an article proposing that “smart skills” replace soft ones and “sharp skills” replace hard ones.

I believe the semantics matter—and Lera Boroditsky, an associate professor of cognitive science at the University of California San Diego, agrees. “We can drastically change someone’s perspective by how we choose to talk about and frame something,” she says in an article in Scientific American. By using specific words and phrases, we are “cuing others to think about it in a certain way.”

While sharp skills are essential for business graduates, the smart skills sometimes are more difficult to master, so those are the ones I am going to concentrate on in this article. My personal mantra is, “The job is easy, the people are not.” People are complex algorithms, affected by factors such as mood swings, hunger pains, and external circumstances. We must develop our smart skills as a way to augment our own humanity.

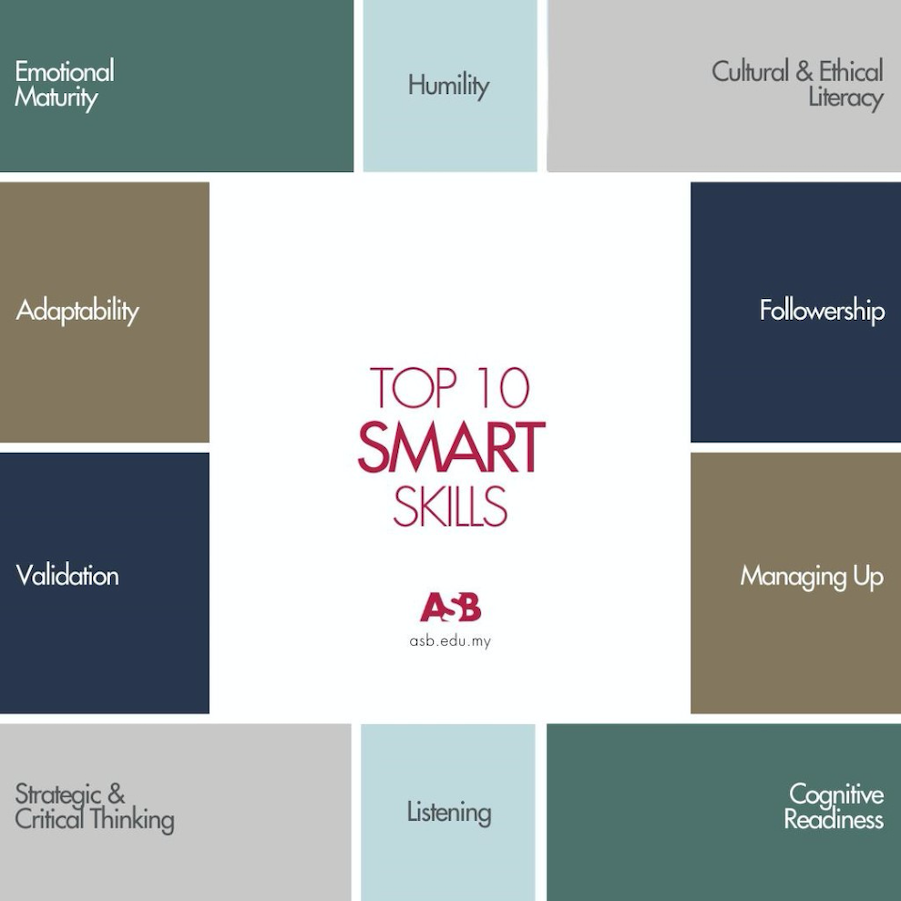

Identifying 10 Key Skills

As the faculty director for the Action Learning Program at the Asia School of Business (ASB) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, I send students all over southeastern Asia and beyond to solve business challenges in experiential learning projects. I see them struggle to deal with diverse peers and hosts, to manage their emotions in a climate of constant change, and to adapt to new circumstances. I find that cultivation of 10 specific smart skills will help them on their journeys:

1. Emotional maturity: the ability to understand and manage their own feelings as well as the feelings of others.

Emotionally mature people are able to regulate their impulses, and they don’t allow a conflict to get the best of them. Even during an argument, they act with empathy; they take responsibility for themselves, and they recognize when other people have different points of view. They recognize that they will need to engage in learning and self-improvement throughout their lifetimes.

2. Validation: the ability to provide or ask for affirmation that feelings or opinions are worthwhile.

Working with people is a constant exercise in validation. Validation can calm fears and concerns, reduce or resolve conflicts, and encourage people to open up to others. In a 2018 article, media personality Oprah Winfrey commented, “I’ve talked to nearly 30,000 people on this show, and all 30,000 had one thing in common: They all wanted validation.” She added that offering validation is the simple act of letting people know: “I see you. I hear you. And what you say matters.”

3. Listening: the ability to focus completely on what other people are saying, understand their messages, and respond thoughtfully.

All of us have been in situations where we felt unheard or misunderstood, so we should recognize that the people around us feel the same. I ask my students to listen more—to focus on the problems before they try to find the solutions.

4. Followership: the capacity or willingness to follow a leader, a mission, or a cause.

While business schools often promote good leadership, people follow more than they lead, so business programs also should emphasize good followership. Followers don’t blindly accept everything a leader says, but they actively participate in organizational goals, and they help leaders succeed. Even when an organization has a strong leader, if team members aren’t able to carry out the leader’s vision, the organization will fail.

5. Managing up: the ability to develop a good relationship with a superior; the ability to solve problems for a variety of stakeholders.

The first definition is the classic one, and the second is the more modern interpretation. One of the biggest challenges my students identify in their action learning projects is managing a wide array of stakeholders: their hosts, faculty advisors, faculty directors, business coaches, and each other. They often ask me, “Who is the person I should listen to? Who is my ‘boss’?” The truth is that managing up requires balancing the needs of multiple competing stakeholders, often simultaneously.

6. Humility: the ability to recognize your value and the value of others while realizing that we all are where we are because we are sitting on the shoulders of others.

People with a sense of humility see that they can always learn more and achieve more—and they realize that others have the same ability to grow. The president of ASB, Charlie Fine, says, “The world is full of smart and arrogant people. I want to work with the smart and humble ones.”

The truth is, most MBAs lack humility. They must constantly remind themselves that the more they know, the more they will realize how much they don’t know. This knowledge keeps them humble and encourages them to keep learning.

One of the biggest challenges students identify is managing a wide array of stakeholders: their hosts, faculty advisors, faculty directors, business coaches, and each other.

7. Adaptability: the willingness to change with changing conditions.

As Charles Darwin said, the only species that survive are the fast and adaptable ones. Have you seen any dinosaurs lately? If humans don’t evolve, they will disappear, too. Professionals with strong adaptability skills will survive. The rest will probably spend their time in Jurassic Park.

8. Cultural and ethical literacy: the competence to recognize and respect differences among people.

These might include differences in background, race, religion, or country of origin. Every group will have its own set of attitudes and values, so professionals must be able to identify moral and ethical contexts and dilemmas. This particular smart skill is more critical than ever because of the global expansion of the workforce.

9. Strategic and critical thinking: the process of conceptualizing, analyzing, synthesizing, and applying information.

Critical thinkers evaluate and deploy knowledge to reach a goal and develop a plan for execution. They are able to solve complex problems in the absence of blueprints and standard operating procedures. Whenever I ask employers what skills they value most, strategic and critical thinking come out on top.

10. Cognitive readiness: the mental preparation to sustain competent performance.

Cognitive readiness encompasses the skills, knowledge, motivations, and personal dispositions people need to operate in unpredictable environments. Leaders and their teams have to be prepared to face unpredictable and ill-defined challenges in situations that are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. This is a hard skill to master, and it requires professionals to be prepared on a constant basis.

Developing Skills Through Project Learning

How can business schools teach these 10 essential smart skills? At ASB, we impart them through our Action Learning Program, where students first go on-site to tackle complicated problems, and then reflect on what they’ve learned in the process.

During their 20 months in our program, MBA students participate in five extremely varied experiential learning opportunities. Projects range from developing marketing strategies for multinational corporations to devising economic development plans for indigenous people living in the rainforest. Students might think it will be challenging to travel to a remote corner of the Philippines to formulate an integer programming model for scheduling at a food processing factory. But believe me when I say it’s easier for them to build the programming model than it is for them to develop the smart skills they will need to work with factory personnel who might come from very different backgrounds.

Students start to recognize obstructive behavior patterns in themselves and others. They work harder to develop their empathy, humility, and critical thinking abilities.

For each project, students make three trips to the site—first to refine the project scope, next to collect data and begin problem solving, and finally to implement solutions. Each time they return to campus, they meet with faculty and reflect on their next steps.

I have found that, during their first on-site experiences, students learn when to listen, when to speak, and how to keep their egos in check. They discover that none of them is the smartest person in the room. And they learn to manage their emotions when they are working seemingly endless 12-hour days.

Before they go on their second on-site visit, students undergo 360-degree evaluations that help them understand themselves and others. Many have noted how helpful such evaluations can be—in fact, first-year MBA student Arun Chakraborty said his experience sparked a paradigm shift. He said, “It allowed me to understand my teammates’ perspectives and how changing my approach could help them understand me better.” Similarly, Franco Bravard, a second-year MBA student, learned “that my identity is not under attack when receiving feedback, and I have to appreciate when the other person is trying to help me.”

By the time students return for their second visits, they have started to recognize obstructive behavior patterns in themselves and others. They work harder to develop their empathy, humility, and critical thinking abilities. As they continue to go through the action-and-reflection cycle, they develop their cultural literacy and learn about various political and strategic perspectives. They get opportunities to test their new skills in a wide range of industries, companies, and settings. By the time they graduate, they are principled and market-ready leaders who are smart and sharp in action.

Navigating the Future

ASB was founded in 2015, so we are just at the beginning of our journey, and we have much more to learn. But we confidently believe that the next generation of management practitioners will need a full suite of smart skills to navigate the complex ecosystems that drive today’s economy.

Loredana Padurean is the associate dean and faculty director for Action Learning, Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Asia School of Business in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The article was written with editorial input from Charles Fine, CEO, president, and dean of ASB. The authors are grateful for the input offered by ASB student Devika Manoj Made and ASB professors Willem Smit and Shien Jin.

Loredana Padurean is the associate dean and faculty director for Action Learning, Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Asia School of Business in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The article was written with editorial input from Charles Fine, CEO, president, and dean of ASB. The authors are grateful for the input offered by ASB student Devika Manoj Made and ASB professors Willem Smit and Shien Jin.