What’s Your Business School’s SDG Score?

- To create a meaningful benchmark, we drew from multiple data sources to analyze how committed business schools are to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, based on their research output, and how resources play a role in a school’s SDG engagements.

- The schools in our sample paid greatest attention to the SDGs related to ending poverty, promoting peace and justice, and reducing inequality.

- Although schools with bigger budgets and faculties tend to have higher SDG ratios, even schools with more limited resources can enhance their SDG profiles if they adopt targeted strategies and foster sustainability-centric cultures.

At a time when sustainable development is at the forefront of many national agendas, academic institutions will play critical roles in creating a better future. This is particularly true for business schools, where faculty are giving greater attention to societal impact in their research and teaching.

But while business schools have made public commitments to helping the world meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), how many academic administrators have a good overview and narrative of how well their schools’ activities support this objective?

Recently, we conducted a study to provide greater insight into this question. Our study leverages an extensive dataset from AACSB and SDG Metrics, a dashboard developed by the Rotterdam School of Management (RSM) at Erasmus University in the Netherlands. Focusing on a selective set of public business schools in Europe registered in the AACSB data hub, we examined some key parameters such as operational budgets, faculty sizes, SDG-related publications, and total publication counts to provide new insights into how resource allocation influences SDG-focused academic output.

With this data in mind, we looked at a range of factors. In particular, we first plotted schools on a range of 0 to 2.0, correlated to the size of their budgets (in the context of this study, 1.0 in this range denotes a budget of 100 million USD). Next, we considered the percentage of publications each school produced that were related to at least one of the 17 SDGs, as well as how many of the 17 SDGs each article addressed.

Other metrics on the dashboard, but not represented in this article, include an SDG Profile, which describes how the SDGs are distributed across a school’s research and programs; SDG Significance, a more normative metric that indicates the overall power of a program’s SDG relatedness, giving publications with high SDG relatedness a higher weight; and a mean SDG score based on the factors mentioned above.

Our research provides data to guide educators, policymakers, and stakeholders in the higher education sector in their strategic decisions and policy development related to the SDGs.

Which Goals Are a Priority?

First, we broke down how the 73 European business schools in our sample balanced their research and curricula across critical sustainability areas. These schools were selected because they all had had at least one continuous improvement review visit as part of their initial AACSB accreditation visits, and had reported data on their operation budgets and faculty totals for the last AACSB Business School Questionnaire survey.

In our evaluation, we adopted the terms that the Stockholm Resilience Centre uses in its “wedding cake” model, which separates the SDGs into three distinct layers:

- The biosphere layer includes environmental SDGs such as clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) and climate action (SDG 13).

- The society layer encompasses crucial societal goals such as quality education (SDG 4), good health and well-being (SDG 3), and gender equality (SDG 5).

- The economy layer includes goals such as industry, innovation, and infrastructure (SDG 9) and decent work and economic growth (SDG 8).

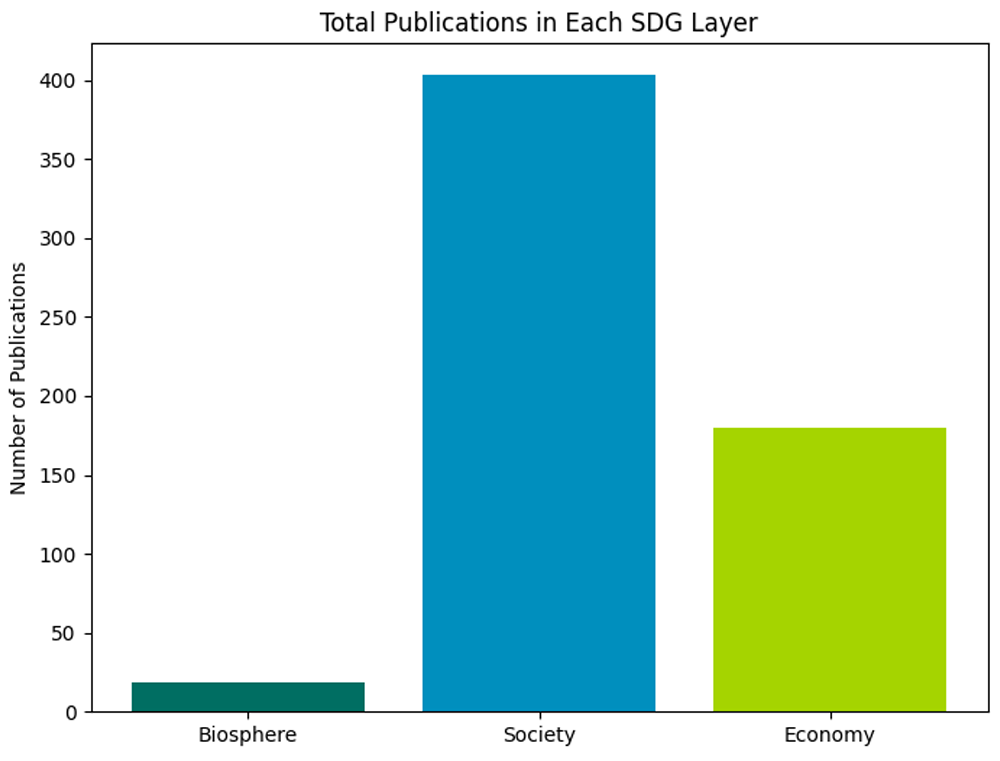

For example, according to our data, the schools in our sample collectively produced only 19 publications on topics related to the biosphere layer—the lowest of all the three layers. This suggests that while some schools are paying attention to fundamental environmental sustainability goals, there remains significant room for increased focus in this critical area.

By contrast, the society layer witnessed the highest SDG relatedness, with a total of 403 publications. This reflects an emphasis on important societal issues within the academic outputs of these schools and highlights their contributions to addressing key social challenges as represented by the SDGs.

A greater focus on the society layer could be shaping the research agendas of these institutions, steering them toward topics related to societal well-being in response to stakeholder expectations.

It is possible that the greater attention to the society layer among the European business schools in our dataset might be influenced, at least in part, by AACSB's growing emphasis on societal impact in business education. This trend could be a reflection of a wider shift toward socially responsible and sustainable business practices. Additionally, this focus could be shaping the research agendas of these institutions, steering them toward topics related to societal well-being in response to global challenges and stakeholder expectations.

Finally, it is not surprising that the institutions in our sample engaged substantially with the economy layer, with 180 publications. This underscores their commitment to economic and industrial development goals, which are cornerstones of business education and research and in line with the traditional focus of business schools.

Overall, the numbers show that, across all publications, the SDG goals that the schools in this set focused on most were SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), and SDG 10 (reduced inequality).

More Resources, Greater Contributions

Not surprisingly, the data show significant correlations between a school’s resources—notably, operating budget, size, faculty count, and overall research power—and the extent of its focus on the different layers of the SDG wedding cake model. This reflects how crucial financial resources are in enabling and expanding research and initiatives targeting sustainable development.

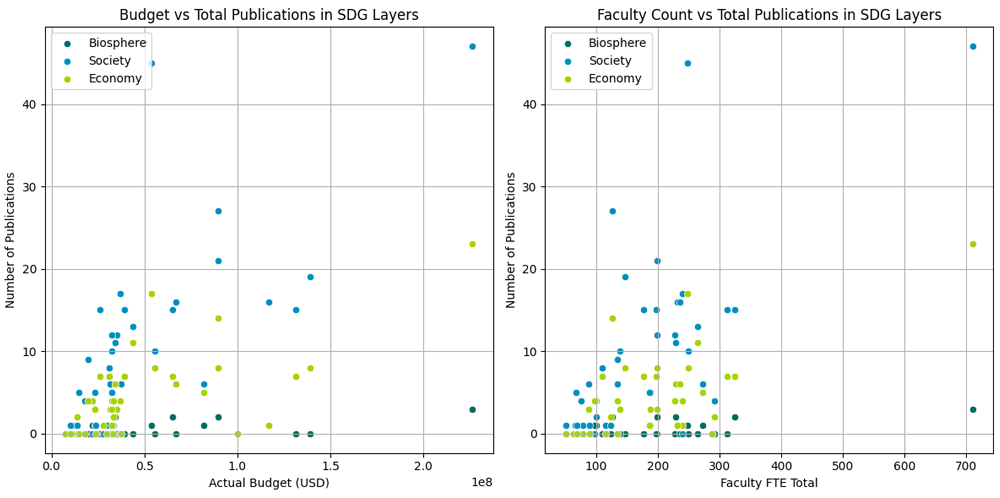

As in other areas, we have mapped the number of a school’s SDG-related publications to its operating budget based on a range of 0 to 2.0 (with 2.0 denoting the largest budgets). With some exceptions, schools with larger budgets tend to produce a greater number of publications, as shown below.

Similarly, schools with larger numbers of full-time faculty tend to make greater contributions to SDG-related research. More specifically, schools with larger budgets and greater faculty counts tend to have a broader engagement across all layers, with a notable emphasis on the society and economy layers, as noted below.

Similarly, schools with larger numbers of full-time faculty tend to make greater contributions to SDG-related research. More specifically, schools with larger budgets and greater faculty counts tend to have a broader engagement across all layers, with a notable emphasis on the society and economy layers, as noted below.

This trend suggests that more substantial financial resources and larger academic workforces enable these institutions to diversify their research and educational efforts, covering a wider array of SDGs. However, despite ample resources, the focus on the biosphere layer remains relatively modest across most schools in this set.

This disparity indicates that while resource availability is a crucial factor in determining the breadth of SDG engagement, it does not automatically translate into a balanced focus across all environmental, societal, and economic sustainability goals. Moreover, we saw several schools at the lower end of the resource spectrum produce high numbers of SDG-related publications.

These insights underscore an opportunity for schools to strategically allocate resources and make a more deliberate institutional emphasis on clusters of SDGs that align with their institutional missions. There is a particular opportunity for schools to rethink and bolster more (interdisciplinary) research and initiatives addressing environmental sustainability challenges within the biosphere layer.

Yes, Resources Matter—But So Does Culture

Although more resources and bigger faculties correlate with greater SDG relatedness of research, the study reveals that these factors do not fully account for the extent of SDG engagement, as indicated by the outliers in the data. For example, a much broader level of engagement with the SDGs is demonstrated in schools that publish biannual Sharing Information on Progress (SIP) reports that are required of them as signatories of the U.N.’s Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME).

The seven PRME SIP reports that Copenhagen Business School has published since 2010 are a very nice example of this broader sustainability reporting practice. These reports show a long tradition of sustainability engagement across the school, in all core business dimensions of education, research, and engagement. There are many such inspirational collections of PRME reports that illustrate the long-term practices of PRME member schools.

Schools that foster sustainability-centric cultures can significantly enhance their institutional impact potential for the SDGs, independent of the resources they have available.

Additionally, there is notable variability in SDG focus among schools with similar resource levels, reflecting the influence of individual institutional strategies and priorities. Some schools, for instance, show a stronger engagement with SDGs related to entrepreneurship and innovation, areas that align with their academic strengths.

This variability has implications for how business schools approach sustainability in their curricula and research agendas. Mainly, these findings emphasize the need for business schools to have a strategic approach in how they allocate their resources toward sustainability goals. The study also suggests that schools that foster sustainability-centric cultures can significantly enhance their institutional impact potential for the SDGs, independent of the resources they have available.

Need for Future Research

This collaborative study by AACSB and RSM’s SDG Metrics marks a step forward in understanding the dynamics between resource allocation and SDG engagement in business schools. It highlights the critical role of resources in driving SDG-focused research, as well as the importance of strategic choices and institutional values in shaping sustainable futures.

Just as important, it demonstrates the strategic value of combining multiple data sources into a meaningful analysis for schools, helping deans understand their schools’ relative position among other schools on key business dimensions such as SDG engagement.

Looking forward, we believe that future analyses could explore areas that further enrich our understanding of the global academic landscape’s response to sustainability challenges. These include longitudinal analyses to track changes over time, comparative studies across regions, and qualitative research that delves into the motivations and strategies behind schools’ SDG engagement.

As the world grapples with sustainability challenges, the contributions of academic institutions remain crucial, particularly in regard to shaping future business leaders and practices. Further examinations into business schools’ SDG-related output will bring greater clarity to how they can most effectively focus their strengths on realizing the SDGs.

AACSB and SDG Metrics plan to engage in more collaborative analytics that build on the findings presented above. Additionally, we invite people across the business education community to share the relevant data they possess about their schools’ SDG-related activities and to work with us on future research projects. Together, we can accelerate the societal impact of business schools worldwide.