Gamifying Sustainability

Does it take more water to produce beef or chocolate? If you guessed chocolate, you’d be right. You’d also be one step closer to winning a board game called Terwa, which was created by a team of students at the University of Mannheim Business School in Germany. They were part of a new class called Sustainability Games, which uses a game design approach to foster sustainability awareness in future leaders. The class was described in a submission to AACSB’s 2021 Innovations That Inspire initiative.

The interactive class was the brainchild of Carmela Aprea, chair of economic and business education, and Laura Marie Edinger-Schons, chair of sustainable business. Because the world is threatened by urgent issues such as climate change, species extinction, and water scarcity, the two professors believe that business schools must teach students how to be proactive changemakers who can develop more resilient economies and societies. They further believe that to truly empower students as changemakers, schools need to employ innovative learning methods that engage learners in ways that more traditional methods do not.

Goals and Games

The class is structured so that students learn simultaneously about sustainability and game design, splitting their time evenly between the two topics. In the first class session, Aprea and Edinger-Schons introduce students to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as the basics of game design. In that same session, students form four- to five-person teams and decide which SDG they want to focus on for their games.

Students spend the next four weeks researching additional materials that help them gain a deep understanding of the sustainability problem they want to address. They also learn game design theory through classroom discussions and through books such as Jesse Shell’s The Art of Game Design and Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop. As they begin developing their games, students share their ideas with their classmates, who offer suggestions and feedback.

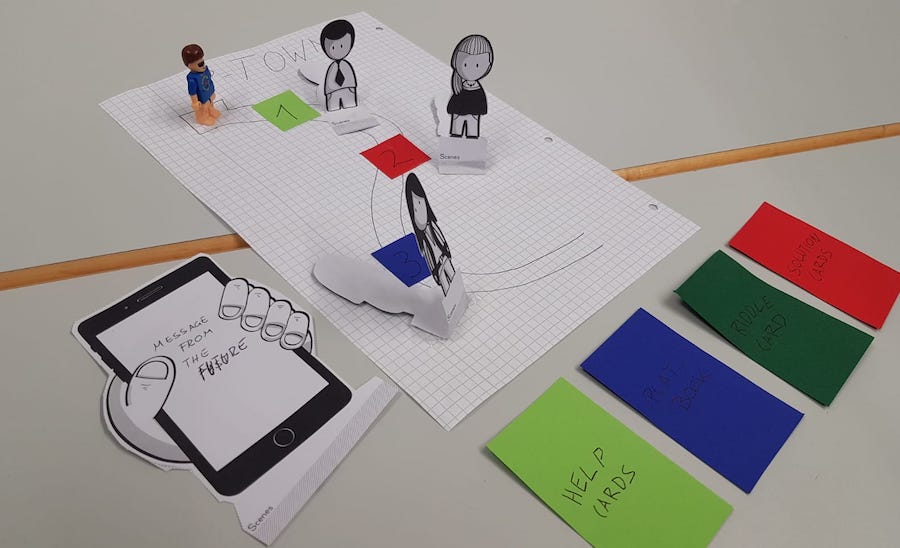

Students work on their board games to teach sustainability concepts. Photo by Laura Marie Edinger-Schons

To help students concurrently explore their chosen SDGs and keep track of their design process, the instructors have each team fill in a sustainability game development canvas. The canvas includes four sections: the sustainability problem that students want to address, the target groups they hope to reach, the learning goals they have for players, and the mechanics of their games.

As long as students include a sustainability element, they can base their games on well-known commercial models. They also can choose whether they want to develop analog or digital versions. During the first class, most students originally planned to create analog games, though some eventually decided to create digital versions instead. In future classes, Aprea and Edinger-Schons intend to introduce tools such as Scratch, which make digital game design simpler.

However, they have no plans to try to steer students toward digital versions. “Given that our focus is to support students’ deep understanding of the sustainability problem by designing games, we want to keep technical requirements to a minimum,” Aprea explains. “And analog games are quite popular, even among young people.”

The City in the Desert

Once their games are completed, teams produce project reports that describe and justify all game decisions, and they include their sustainability game development canvases as appendices in their reports. Students also create videos showing how their games work.

For instance, in the video about Terwa, the students demonstrate how their analog board game illustrates SDG 6, which aims to ensure the global availability and sustainability of water. The game is set in a desert city that has a lake of blue beads in the middle. As players advance along the board, they draw cards that represent various activities, and they must guess which activity takes less water to consume. If they guess correctly, they only have to withdraw a small number of beads from the lake; if they’re wrong, they have to take more beads. Players also can draw question cards that test their knowledge of water and how to conserve it. If they answer correctly, they can put beads back in the lake. The winner is the player who arrives at the lake with the fewest beads.

Aimed at children who are 12 or older, Terwa is meant to be a fun way to help players understand the water footprints of common products. It is also designed to teach decision making skills and compassion for people with fewer resources.

Since its design, Terwa has been used in a museum environment to teach about water conservation. It also has been made publicly available on YouTube—something the instructors would like to see happen more often in the future.

“It would be great to ask students right from the start whether they would be willing to make their produced materials available for open access so other educational institutions can use them,” says Edinger-Schons. “Of course, this cannot be a mandatory requirement, because the games are the students’ intellectual property.”

A Few Challenges

The first Sustainability Games class was held in 2020 and encountered a few unexpected glitches. For instance, Aprea and Edinger-Schons originally planned for students to develop prototypes that classmates could play so they could offer constructive feedback. However, COVID-19 forced a reset when classes switched to online learning. For that reason, students had to find their own test players among their circles of friends.

The class raises students’ awareness of sustainability issues, gives them a deep understanding of the challenges related to specific sustainability crises, allows them to identify key stakeholders, and encourages them consider potential solutions.

Students also encountered a few issues around teamwork and collaboration, such as “free rider” group members. “We think it could be useful to be more explicit about this aspect in the future—for example, by having the students present a work plan stating the responsibilities of each group member and submitting a contribution statement at the end,” says Aprea. The instructors also might organize students around specific SDGs as a way to make certain everyone on the team has the same level of interest in the topic.

While some students did struggle at times with both the content and design of their games, the instructors observed that everyone in the class generally was intrigued by both elements. “We found students very motivated and ambitious to learn more about ‘their’ sustainability problems,” says Aprea. “They also were enthusiastic about the creative experience of developing and designing games.”

Wider Impacts

Aprea and Edinger-Schons say the class is designed to meet a number of goals: It raises students’ awareness of sustainability issues, gives them a deep understanding of the challenges related to specific sustainability crises, allows them to identify key stakeholders, and encourages them to consider potential solutions. The class also helps students develop their teamwork skills and their understanding of how games can be used to convey vital topics in an effective and engaging way.

The professors hope that, in the future, student teams will be able to beta test their prototypes with younger players at local schools and older players at educational institutions. These interactions could have benefits for stakeholders at all levels, say Aprea and Edinger-Schons. University of Mannheim students would have a chance to engage in service learning; partner schools would receive support in their own efforts at teaching about sustainability; and society would gain more citizens of all age groups who understand the benefits of sustainability.

Above all, Aprea and Edinger-Schons hope that participating students become future changemakers and catalysts. Says Aprea, “When they are able to reflect on their role regarding the development of more sustainable societies, they will be empowered to take action.”