360 Degrees of Care

In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 forced higher education institutions to transform at an unprecedented pace. Schools rightfully prioritized establishing strategies for online and blended learning, but few of them focused on addressing the well-being of their learning communities beyond ensuring the physical safety of students. And most schools viewed the pandemic as merely a short-term disruption to “the way we do things here.”

However, the coronavirus has forced us to consider many pressing and long-term questions about how universities teach and care for students. As Greta Anderson notes in a September 2020 article in Inside Higher Ed, the crisis has made it clear that we need to address the intensifying mental health needs of students.

Can we experience the pandemic as a transformational force that will help us meet the ever-changing needs of learners? And can we see it as a wake-up call for focusing on the well-being of the learning community?

Core Support

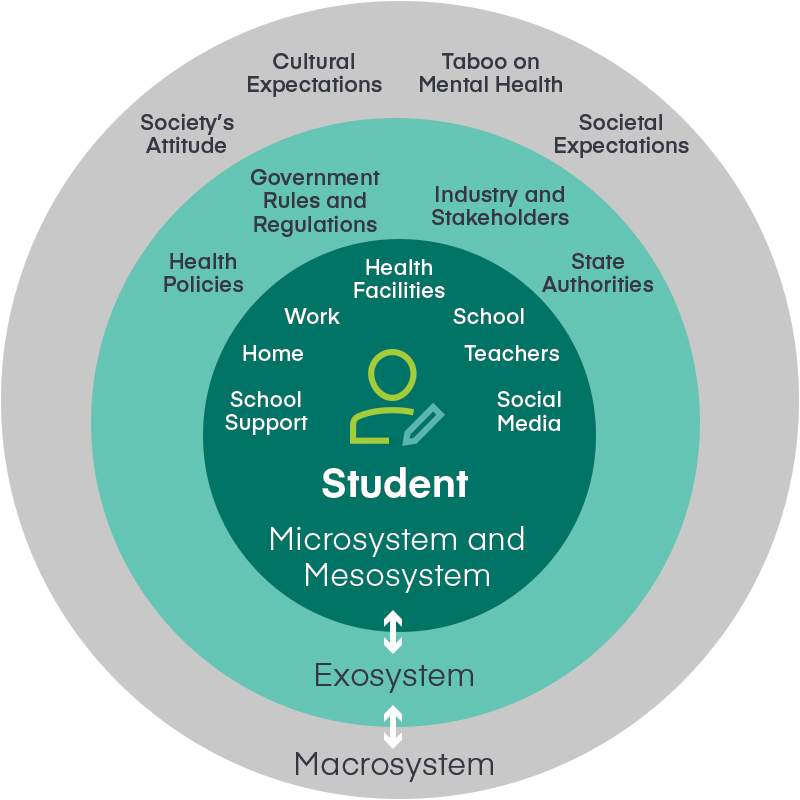

Students do not learn without context. They interact with their immediate and distal environments, which also interact with each other. Drawing on the 2000 work of Urie Bronfenbrenner and Gary W. Evans, who discuss development psychology and social development in the 21st century, I created a graphic model (see Figure 1 below) that shows how students should be at the core of a community that supports them at every level, directly or indirectly.

Figure 1. Creating 360-degree support.

Students are the microsystems—the smallest units within the mesosystem, the surrounding environment that influences their development. Some of the components within this mesosystem, such as students’ home and work environments, are not directly under the influence of the university. Nevertheless, home and university environments do overlap. For instance, when students participate in video calls from their homes, they often are revealing their socioeconomic status, which might make some students feel vulnerable. When learners are also working professionals, they have less flexibility than their peers who are full-time students. The university cannot directly influence less-than-ideal home situations, but when administrators acknowledge that students are working under imperfect conditions, they help create a community of care.

Four other components within the mesosystem are directly connected to the university, and during the pandemic these components have become big parts of students’ communities of care. However, I believe they should be utilized to their fullest extent even in more ordinary times:

Instructors. While delivering subject matter is their No. 1 priority, instructors also are the agents within the mesosystem that are the closest to students. Therefore, instructors are the first ones who can extend mental health support. In particular, two small steps can be very effective.

First, instructors can start live or online classes with a 10-minute ice-breaking activity to let students talk about their emotions and their daily lives. Sharing experiences and feelings can have wondrous effects on students’ well-being, motivation, and engagement overall, according to an article by Mariana T. Guzzardo and co-authors in Innovative Higher Education. During the pandemic, it became clear that online environments might increase instructor-student interactions in a way that isn’t possible in live classes—and wasn’t considered essential before the crisis.

Second, instructors can provide highly personalized feedback to students. This is especially true in asynchronous classes, where teachers can establish rapport with students by engaging with them in discussion forums. These asynchronous sessions help students stay connected to their learning communities whenever it is convenient for them, rather than at a prescribed moment during the week.

Even if professors can’t comment on every student’s post, they should give proper and customized feedback as part of their assessment and grading activities. As Nic Beech and Frederik Anseel predict in an article for the British Journal of Management, the real asset of higher education in the post-pandemic era will be the quality of interaction among students and teachers. In fact, as Hossein Khalili writes in the Journal of Interprofessional Care, as long as engaging instructional designs allow students to stay connected to their online and offline learning communities, they will have healthy ways to maintain human contact. In this case, the challenge is not how to make the switch to online and hybrid platforms—it’s how to excel at delivering engaging educational experiences on those platforms.

Because the pandemic has caused a growing number of students to experience mental health issues, support services have become even more critical to the support community.

The broader university. Even in ordinary times, higher education institutions have diversified responsibilities and competing priorities. They must provide financial and career support for students; encourage their personnel to pursue upskilling opportunities; promote excellence in teaching and learning, often through specialized centers; and establish mentorship for both academics and students.

But during a crisis, these institutions have to take on even more tasks. They must deliver clear and consistent messaging; protect the physical, mental, and emotional health of students; make strategic and prudent decisions to establish stable educational delivery; and create a disaster plan and crisis management procedures. All these steps are part of creating communities of care.

Student support services. Though part of the larger institution, this department plays a distinctive role in the mesosystem. Because the pandemic has caused a growing number of students to experience moderate to severe mental health issues, support services have become even more critical to the support community.

Among other things, these departments help students develop empowering strategies, such as cultivating growth mindsets, honing coping skills, increasing resilience, and setting goals, according to research by Jaqueline Dohaney and co-authors. Support services departments can use a range of different channels—such as official university websites, in-class announcements, social media, and online brochures—to encourage students to use these services.

Despite the fact that higher education institutions have limited budgets, they can develop creative and low-cost solutions to address students’ mental health needs. For instance, Guzzardo and her co-authors suggest that schools could reskill staff members and boost their trauma response expertise. One way to do this might be by hosting guest speakers over lunch events. Such efforts may help schools put preventive processes in place to support student well-being before there is a crisis.

Mental health facilities. Until recently, mental and emotional health generally has been considered an off-limits topic in academia. Therefore, when the coronavirus crisis resulted in an exponentially growing demand for mental health services, many schools were caught unprepared, Keith Albertson writes in ISE Magazine. On the other hand, as Dohaney points out, the fact that more students are seeking mental health support indicates that there is less of a stigma attached to such issues.

While the pandemic made it almost impossible for students to physically seek out health services, it did have one positive side effect: When institutions immediately transitioned their services to an online format, they made it easier for students to receive help. Even students who have gone back to their hometowns have online access to the psychiatrists and psychologists at their universities.

Many healthcare professionals have also found ways to deliver services to larger learning communities through online group counseling, seminars, workshops, declarations, and their social media presence platforms. To provide a framework for schools dealing with such scattered resources, the American Council on Education has put together guidelines that focus on student well-being and safety.

Outer Circles of Care

Outside of the mesosystem are two additional rings that support and affect students as they pursue their educations. The first is the exosystem, which consists of the following external stakeholders whose influence, while indirect, can be powerful and broad:

Government institutions. These agencies can work hand-in-hand with health authorities to identify high-risk groups that are prone to psychological problems. At that point, writes Souvik Dubey and co-authors, schools can design early intervention processes to identify and help these students.

Industry leaders. Academia creates a win-win situation when it partners with top executives and local business leaders. For example, if graduate students serve as consultants for struggling enterprises, the students gain work experience while the businesses receive useful guidance. The pandemic forced some internships to be conducted remotely, but even these arrangements benefited both parties. Businesses enjoyed access to a broad range of talent, and students were exposed to variety of work environments.

Alumni. Past graduates participate in communities of care by serving as bridges between industry and academia. They also provide current students with work experience, mentorship, and ad hoc advice.

A culture’s underlying assumptions, values, expectations, and taboos affect students in invisible but profound ways.

Today’s graduates are entering a more competitive world that offers diminished opportunities for employment, as Sandeep Krishnamurthy points out in the Journal of Business Research. The involvement of industry leaders, local business owners, and alumni will help students gain work experience and reduce the burden of the job search, which will contribute to their overall well-being.

Beyond the exosystem is the macrosystem, in which a culture’s underlying assumptions, values, expectations, and taboos affect students in invisible but profound ways. These implicit factors can be difficult to change, yet crises may force some powerful shifts.

During the current pandemic, this shift has been particularly visible in the area of mental health. In some societies, it is still taboo to discuss mental health issues, but this attitude is changing as COVID-19 pushes more students to be open about their struggles.

However, the pandemic also made some students feel more vulnerable by highlighting where they fit within the macrosystem. While online education became the only option during the pandemic, it also revealed discrepancies among students in terms of socio-economic status, housing conditions, and cultural differences. For some students, having these inequities exposed to the public eye can be distressing. Therefore, when administrators design support systems, such systems cannot just be student-centered and personalized. As J. Chang and co-authors write in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, these measures also must be culturally sensitive.

A New Opportunity

The worldwide pandemic has created many barriers to student success, but it also has encouraged school administrators to question “the way we do things here.” If we are to create true communities of care, we must work from a 360-degree perspective. We must stay more deeply connected with students and take collective action at every level.

Let us use the destructive power of the pandemic as a step toward transforming student well-being in higher education. Let all stakeholders brainstorm ways in which they can contribute to the creation of communities of care. I strongly believe that we can make this our New Year’s resolution for 2021. Our actions can impact masses of students and leave a positive mark on their learning and on their lives.