Can the Biological Clock Stop the Tenure Clock?

In 2009, the three of us analyzed the tenure clock policies at universities in the U.S. at AACSB-accredited business schools. We searched websites looking for identifiable policies relating to family-related events such as the birth of a child, adoption of a child, or placement of a foster child. Ten years later, we performed a similar search because we wanted to know: Have universities made progress in their adoption of family-friendly tenure-clock policies? The answer is yes—but not enough.

The progress has coincided with a significant push for such policies across the industry. For example, in November 2001, the American Association of University Professors produced its “Statement of Principles on Family Responsibilities and Academic Work.” In the statement, the AAUP calls on U.S. higher education institutions to make their policies “sufficiently flexible to permit faculty members to combine family and career responsibilities in the manner best suited to them as professionals and parents.”

In a 2002 article in The Chronicle of Higher Education, the topic was addressed by Joan Williams, a distinguished professor of law and founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California. Williams argues that schools have an ethical and legal responsibility to ensure that department chairs and members of promotion and tenure committees are aware of the parental leave and tenure clock extensions their faculty can use, as well as the impact that such use has on tenure and promotion expectations.

In a 2005 study, the University of Michigan’s Center for the Education of Women (CEW+) found that research-oriented institutions provided nearly twice as many family-friendly options as other institutions. This was true even though they were less likely than their counterparts to employ women faculty, who would likely benefit from these policies the most.

Business schools might be especially inclined to prioritize family-friendly policies, because disciplines such as accounting and finance face extreme shortages of terminally qualified faculty candidates. In addition, as business schools attempt to achieve gender equity, they will need to make their tenure processes more family-friendly if they want to recruit and retain faculty—especially women.

Below, we explore three questions. First, are university websites more transparent now than they were 10 years ago when it comes to posting policies related to tenure-clock extensions for child-related events? Second, are certain types of institutions friendlier toward family-related events? And, finally, what steps can schools take today to make academia even more family-friendly in the future?

What the Data Show

We included 164 institutions in our 2009 study and 175 institutions in our 2019 study. In both years, about 75 percent of the schools we studied were public universities. About 45 percent were research-intensive institutions, as defined by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education; the remainder were generally classified under Carnegie as Master’s Colleges and Universities Level I (larger institutions that award more than 200 master’s degrees each year).

In our analyses of institutional websites, we looked for references to key tenure clock extension policies. This would include information about the school’s eligibility requirements, approval process, and limitations. Using this information, we divided institutions into three categories: automatic, where extensions are granted automatically for child-related events such as birth or adoption; by request, where extensions can be requested for these events; and not available, where the information is extremely vague or absent altogether.

It should be noted, however, the fact that this information is missing or not easily found on a school’s website does not necessarily mean the school does not offer family-friendly tenure extensions. For this study, we interpreted the fact that a school openly includes this information on its website as a clear signal that its leaders both see the value of family-friendly policies and are transparent in communicating those policies.

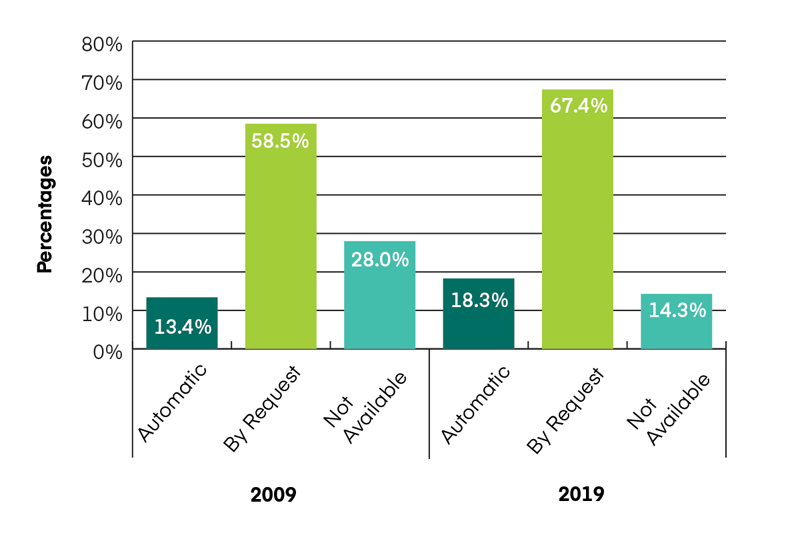

When we compared our results, what we found was encouraging. From 2009 to 2019, the percentage of automatic institutions rose from 13.4 percent to 18.3 percent. The percentage of by request institutions rose from 58.5 percent to 67.4 percent. Even more encouraging was that the portion of not available institutions in our sample fell from 28 percent in 2009 to less than 15 percent in 2019. (See Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1: Availability of tenure clock extension policies on institutional websites in 2009 and 2019.

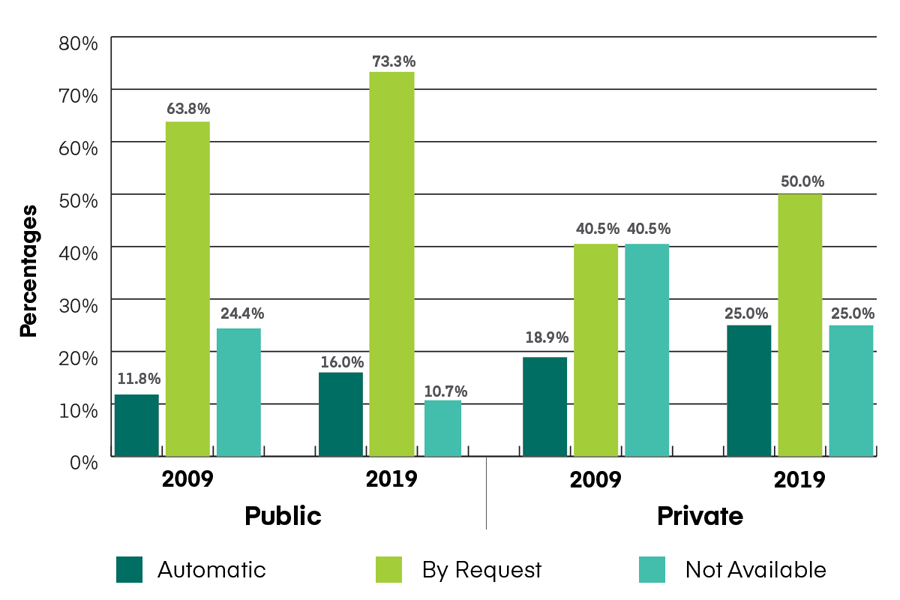

But are certain institutions making more progress than others? Intuitively, it would make sense that public institutions would have more family-friendly tenure extension policies, simply because they are more likely to be subject to both governmental authority and public scrutiny.

Overall, the data show this to be true. In 2019, only 10.7 percent of the public institutions in our sample did not have relevant information evident on their websites, down from 24.4 percent in 2009. That’s compared to 25 percent of private institutions, down from just over 40 percent in 2009. (See Figure 2 below.) The decline in the not available category could be the result of institutions either establishing and publicizing new family-friendly extension policies or merely taking the extra initiative to communicate existing policies on their websites.

Figure 2: Availability of tenure clock extension policies in 2009 and 2019 at public and private institutions.

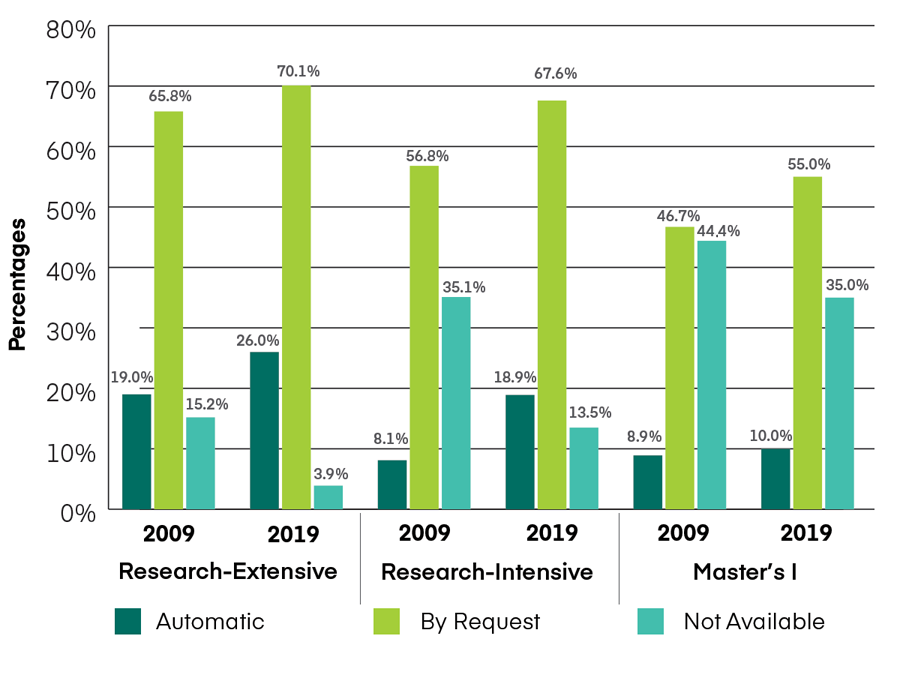

It also would seem logical that research-extensive and research-intensive institutions would be less friendly in their tenure clock extension policies than Master’s I institutions, because the pressure to conduct research is so much stronger at these institutions. However, our research supported the University of Michigan CEW+ study that we referenced earlier: We found that research-extensive institutions are the most forthright with their tenure extension policies for family-related events. (See Figure 3.)

According to our analyses, 96 percent of them promoted such policies as of our 2019 survey, and more than 86 percent of research-intensive institutions did so. However, even in 2019, only 65 percent of Master’s I universities posted this information on their websites!

Figure 3: Availability of tenure clock extension policies in 2009 and 2019 by Carnegie classification.

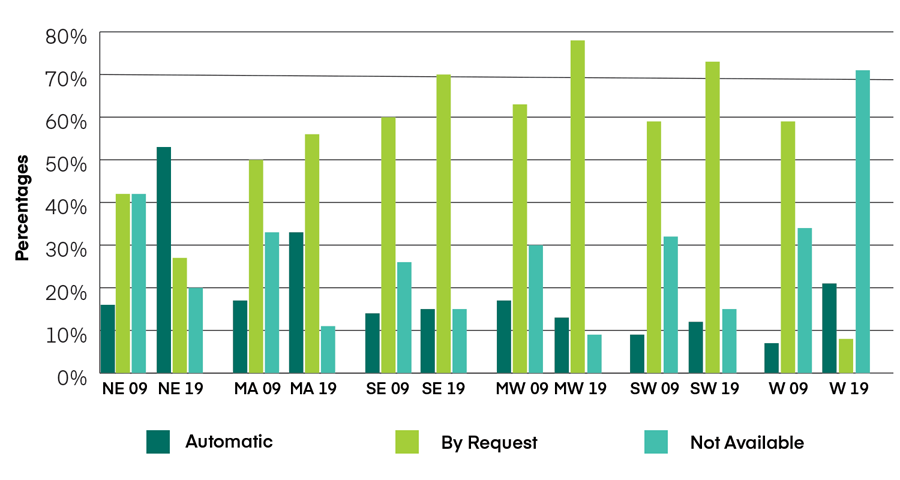

Finally, this study looked at changes in policy transparency and friendliness by location over the last decade. We found that institutions in the Northeastern region showed significant improvement in automatic policies. Those in the Midwestern, Southwestern, and Western regions showed the strongest growth in by request policies.

The percentage of institutions with no information readily available decreased by nearly one-half for institutions in the Northeastern, Mid-Atlantic, Midwestern, and Southwestern regions. (See Figure 4 below.)

Figure 4: Percentage of institutions with automatic, by request, and unavailable tenure clock extension policies in 2009 and 2019 by U.S. region.*

*Northeastern (NE), Mid-Atlantic (MA), Southeastern (SE), Midwestern (MW), Southwestern (SW), and Western (W)

In terms of which regions have made the most progress, the Midwest was at the top of the list in terms of transparency both 2009 and 2019. The Northeast and West remained at the bottom of the list in both analyses, although both made significant gains.

All regions made substantive progress in moving out of the not available classification. But the greatest improvements in family-friendliness and transparency occurred in the Mid-Atlantic region. In 2009, nearly 67 percent of institutions mentioned their policies on their websites in 2009—in 2019, that number grew to nearly 89 percent.

Call to Action

Given the improvements we have seen over the last decade, where will we be 10 years from now? What can we do now to ensure that progress continues? We believe it will take a concerted effort at all levels of the institution:- Faculty and administrators need to become aware of the policies that exist at their institutions.

- Faculty should push for family-friendly tenure extension policies if policies do not exist—or push for open communication of existing policies if they are not made easily available.

- Human resources personnel should cover these policies during new faculty orientation sessions.

- Universities should ensure that promotion and tenure committees are fully aware of these policies.

- Search committees should ask for this information during the faculty recruiting process and communicate this information to candidates.

If faculty demand these policies, universities will have to respond, especially if they want to recruit the best candidates. And the more we see such efforts now, the friendlier academia will become for all faculty—and their families—in the future.