Did COVID Change Graduate Management Education?

- The demand for graduate management education increased in 2020 and 2021, but mostly for elite schools.

- Test-optional admissions policies attract some students, but make others worry about rigor, transparency, and fairness.

- To make up for declining demand, regional schools could target underserved populations, including Hispanic Americans.

“I see my light come shining from the west unto the east

Any day now, any day now, I shall be released.”

Bob Dylan is my idol. When he wrote these words in 1967, he was expressing his longing to escape from everyday realities. Today, these words could equally reflect our collective desire to be released from the uncertainties caused by COVID-19.

For business schools, the “light” could represent answers to questions that have been raised during the pandemic. What does the future of management education look like? Are the COVID-related changes temporary or permanent? How deeply should we be committed to online programs? How should we respond to rising inequality in our societies and the calls for greater diversity in our classrooms?

At the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC), we have our own questions. COVID forced a natural experiment as schools moved toward test-optional admissions policies. Are such policies here to stay? Will students welcome an easier application process? Or will they fear that test-optional schools will be less rigorous and admit cohorts of reduced quality?

As a global association of business schools, GMAC views these trends through the lens of supply and demand for management education. Our goal is to help graduate management education (GME) generally, and our partner schools specifically, build a stronger, more diverse candidate pipeline. Our mission is to provide the tools and information necessary for schools and talent to evaluate and discover each other.

To achieve these objectives, we collect data in multiple ways: by hosting millions of unique visitors on our digital platforms, by conducting regional outreach and MBA Tour events, and by fielding a comprehensive suite of surveys that cover the full life cycle of a candidate’s journey. Not only do these surveys provide a snapshot of student interest in GME, they also reveal demand patterns by tracking test-taking trends, job availability, recruiter preferences, and alumni careers.

So, is there a light that we see shining? One that will guide us through the volatility and uncertainty that we have experienced through the pandemic?

The answer, I am afraid, remains mixed. At the big-picture level, there are certainly strong signals that candidates are interested in management education and that recruiters are poised to give them rewarding jobs. However, the details show that students remain ambivalent about looser admissions policies and the rush to online instruction.

Demand Is Up

Overall demand for GME, as measured in applications submitted, remains strong. The 2020 application cycle saw a robust increase in total global applications, led by Europe (which jumped by 24 percent) and the U.S. (up 20.6 percent), and somewhat tempered by a decline in Asia (which fell by 7.1 percent as countries went into lockdown).

In 2021, these elevated levels of application volume held up for the market overall, rising by 0.4 percent, but there were significant regional shifts. For instance, Asia rebounded (up 4.9 percent) as economies in that region reopened. But the U.S. saw a decrease of 4.7 percent, while Europe experienced a 1.2 percent decline.

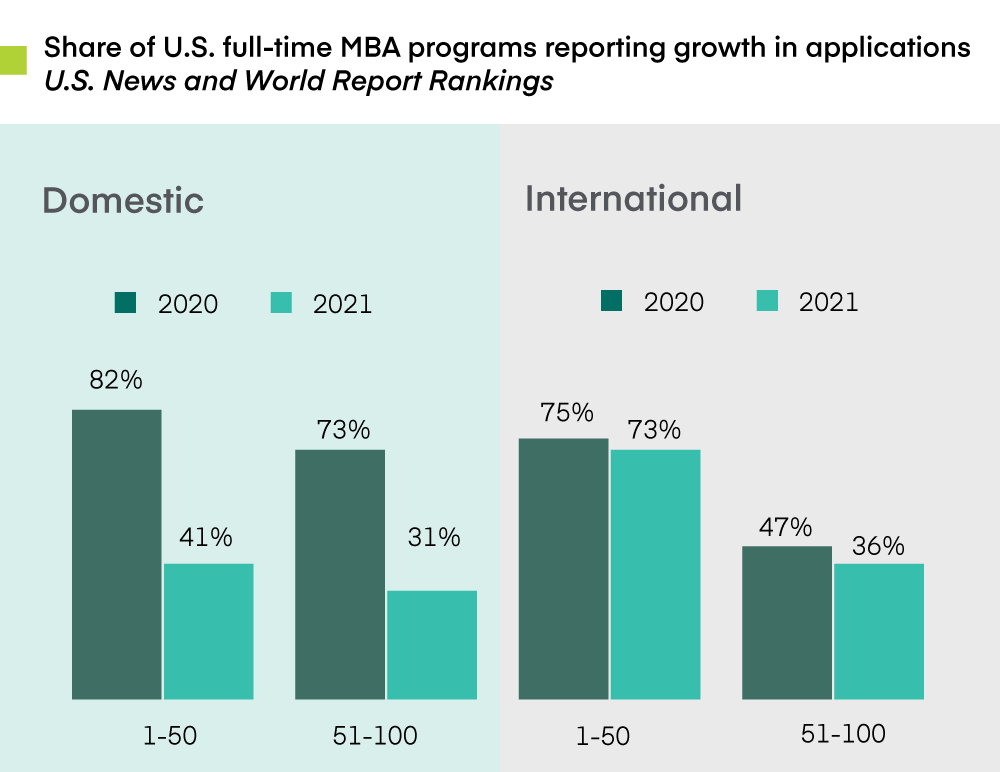

At the same time, most regions saw a drop in domestic demand from students applying to schools in their countries of residence—perhaps a reflection of strong economics and job markets, making work more attractive than school. International demand rebounded strongly but unevenly. Seventy-three percent of the top 50 MBA programs ranked by U.S. News & World Report reported an increase in international applications while only 36 percent of the next 50 reported the same. An analysis using the Financial Times global MBA rankings showed similar trends.

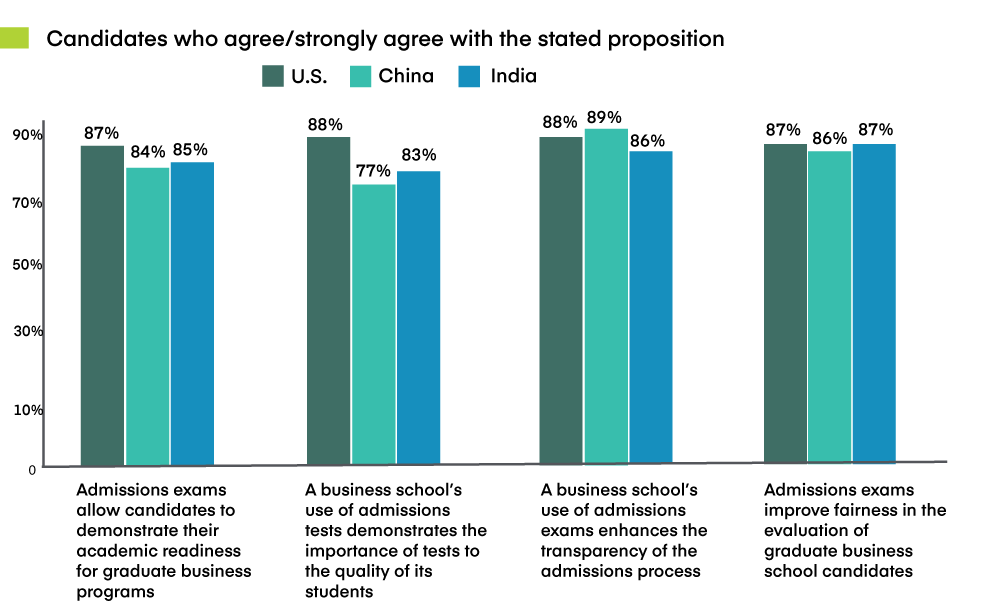

An obvious question is whether looser admissions processes, particularly test waivers, contributed to these increased application volumes. While there was certainly a correlation, at least in the U.S., the sustainability of these practices remains an open question. A large majority of students surveyed by GMAC agree that admissions tests allow candidates to show their readiness for graduate education, demonstrate the importance that schools put on the quality of their students, and enhance the transparency and fairness of the admissions process.

Interestingly, even students who choose not to take a test as part of their applications agree with all of these propositions. The data remain remarkably consistent across different research and sampling methodologies. One conclusion is that test-optional policies at lower-ranked schools might actually be hurting rather than helping these institutions because students are concerned about the signals related to transparency and quality that these policies are sending.

Application Patterns are Changing

While overall demand for GME is still robust, other questions remain. How has student mobility been affected by the pandemic? Are more students and recruiters accepting online programs? How are changing demographics and calls for diversity affecting the classroom and the talent pipeline? Recent research offers some answers.

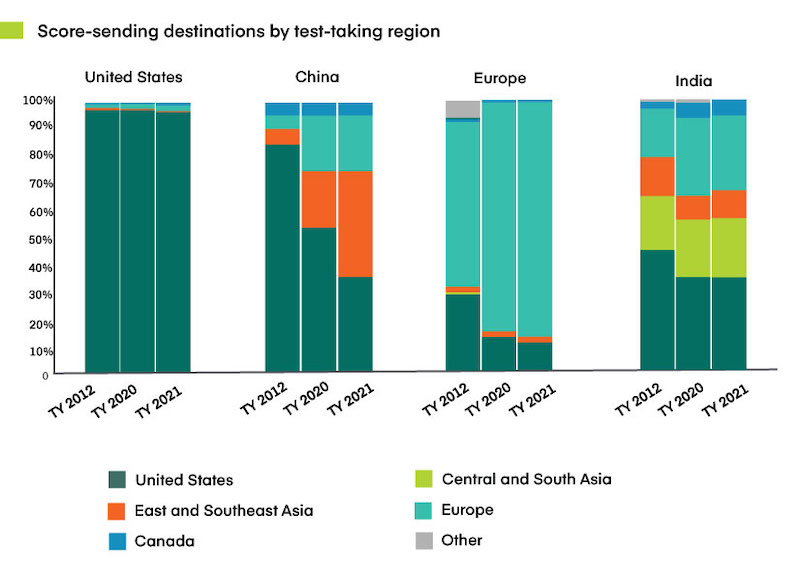

GMAT score-sending patterns indicate that European and Asian destinations are becoming increasingly attractive to prospective students. This is a natural result of the maturing of our industry and the rise of high-quality programs around the world. While it is good for students to have more choices, some schools are suffering the consequences—particularly those in the U.S. that lack the geographical advantages or brand names to compete against these emerging competitors.

Institutions that are losing market share might try to recover by making a greater commitment to online education, which allows schools to compete for students globally. However, a large majority of candidates disagree with the proposition that an online degree provides the same value as one acquired through an on-campus experience.

Will online education gain more acceptance as it becomes mainstream? Perhaps, but only if employers change their perceptions as well: In our most recent Corporate Recruiters Survey, just one-third agreed that their organizations placed equal value on online and in-person degrees.

Moreover, in our Prospective Students Survey, nearly half of domestic students and a third of international students stated that they would consider an online degree from a higher-ranked school versus an in-person degree from a lower-ranked one. Therefore, the schools that are most likely to benefit from more investment in online programs are those that already have a high interest in their in-person offerings.

Diversity Will Be Key

These data show that schools that are not among the brand-name elite are facing some serious challenges. They can’t expect domestic demand to keep growing. They might find that dropping test requirements leads to a decline in applications if students think those policies lead to lower-quality student populations and unfair admissions practices. And they can’t rely on bringing in students through expanded online offerings, which usually only increase interest in brand-name schools. So, what are their options?

For institutions in the U.S., one answer might be to focus on diversity, particularly by developing the Hispanic American pipeline. Our analysis of the data shows that, while Hispanic Americans make up 21 percent of the 24-to-32-year-old population group, they earn only 10 percent of the GME degrees. Assuming the same ratios, and factoring in predicted demographic changes, the number of Hispanic Americans getting GME degrees in the next decade will increase by 68,000.

However, if members of this group began attending business school in the same proportion as the average U.S. population, that number could grow to 406,000. If they participated at the same rate as today’s white Americans, the number would swell to 478,000. As a point of reference, the number of white Americans earning GME degrees over this same period is expected to drop by 148,000 due to population decline.

Other data show that Hispanic Americans are more likely to be first-time college goers, are more rooted in their communities, and are less likely to relocate for GME. For these reasons, they present a ready opportunity for regional schools looking to replace the international cohorts that they depended on in the past. Institutions in other parts of the world similarly might benefit by targeting the populations in their regions that have historically low participation rates in graduate management education.

Questions Remain

Since 2020, we have all been in a long, dark, COVID-related tunnel. Finally, we are seeing a glow ahead. Is it a light that illuminates our path out? Or an oncoming train that could derail our plans?

Our recent research certainly signals strong demand for GME, but some of the changes brought about by the pandemic remain causes for concern. To take advantage of the hopeful signs and to avoid the pitfalls, we must let the data light our way. In both cases, we must be ready to adapt, as Bob Dylan reminds us in another set of lyrics:

“For he that gets hurt

Will be he who has stalled…

For the times they are a-changin’.”