Mental Wellness: A Core Skill for Students

- It has become imperative to focus on mental health as part of the overall educational experience.

- Programs designed to promote mental health should prioritize prevention, competency, and the whole person.

- Such programs also should take a human-centric approach that incorporates empathy and design thinking.

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a well-documented decline in mental health. In the 2021 Work and Well-Being Survey published by the American Psychological Association, the organization noted that 60 percent of workers had reported the negative impacts of work-related stress.

But mental health issues haven’t just taken a toll on business. They’ve also had a major impact on university students, including those enrolled in business schools. The result is that discussions about well-being have become far more frequent in academic settings, and many business school leaders now believe it is imperative to focus on mental health as part of the overall educational experience. Positing on the future of business education in the shadow of COVID-19, Sandeep Krishnamurthy writes, “We are all responsible for the mental health of the student.”

One reason is that business students who have a sense of well-being will be more successful in their classes. But another reason is that these students soon will become business leaders who are responsible for the well-being of their workers. Now more than ever, hiring managers are placing great importance on job candidates with high levels of emotional intelligence. Such individuals are not only self-aware and able to manage their own emotions, but also aware of others and good at managing social relationships.

As Bahia El Oddi and Carin-Isabel Knoop write in an article for Harvard Business Publishing, “Business educators have an opportunity to equip students with the tools and mindsets they need to run psychologically sustainable organizations in the public and private sectors.”

How can academic leaders make sure they are turning out mentally healthy, emotionally intelligent managers who are prepared to lead stable workforces? To craft a portfolio of programming that prevents known stressors while promoting mental wellness, business schools might need to partner with counseling centers, wellness centers, student government associations, and faculty senates. School leaders also need to have a basic understanding of what contributes to mental health—on campus and in the classroom.

A Spectrum of Well-Being

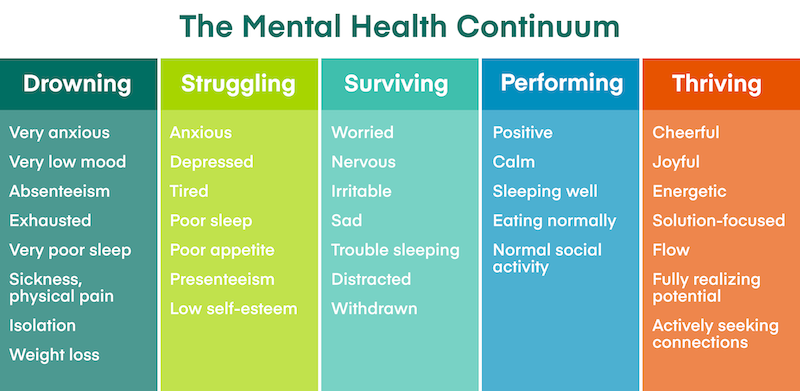

Mental health can be viewed as a continuum that ranges from “drowning” to “thriving.” In each of the five major stages, as outlined below by educational company Delphis, people exhibit specific characteristics, from extreme anxiety to energetic joy.

Business school leaders and educators should focus on students across the entire continuum. At one end of the spectrum, students who are drowning, struggling, and merely surviving warrant pedagogical interventions, but they also should be referred to professionally trained counselors. At the other end of the continuum, students who are performing and thriving should be offered pedagogical and extracurricular interventions designed to promote mental well-being.

As a licensed clinical psychologist who earned a Master of Public Health in health promotion, I took a far from straightforward path to becoming a professor in a college of business. However, my journey allowed me to design a range of courses on mental well-being aimed at undergraduates, graduate students, and executives. Along the way, I identified three priorities for business school leaders to consider as they create programs designed to promote mental health: prevention, competency, and the whole person mindset. Below, I discuss these priorities in detail.

Priority No. 1: Prevention

Mental health issues such as anxiety and depression may impede functioning at all levels, including academic performance. Prevention aims to stall the genesis and development of these issues to ensure that the campus, business school, and classroom climate are psychologically safe and offer support for all. One key to prevention is making sure that women and underrepresented minorities don’t perceive or experience a “chilly climate.”

Prevention also involves screening for early signs of mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and sleep hygiene. Schools can offer these screenings as focused events or as part of larger health and wellness fairs.

In addition, prevention programs can be organized by campus wellness departments or even business school wellness committees. For instance, the mission of the Chicago Booth School of Business Wellness Club is to provide resources on topics such as stress management, work/school life balance, fitness activities, relaxation retreats, and employer wellness programs. The club also provides fun, casual networking opportunities as another way to promote well-being.

Priority No. 2: Competency

Competency aims to increase students’ knowledge, skills, abilities, and sense of agency over key behaviors associated with mental wellness. Competency may be established both inside and outside the classroom, but ideally should be a priority for both settings.

Inside the classroom: Instructors can incorporate belly breathing, mental breaks, and periods for self-reflection into the regular curriculum to promote student well-being. Oddi and Knoop also suggest that faculty who write or teach cases bring up the topic of mental health. As an example, when professors are discussing remote work, they can discuss how to manage priorities, role overload, and role conflict; they also can emphasize the advantages of social support mechanisms that buffer stress.

Outside the classroom: Schools can provide resources and programs designed to help students achieve balance and adjust to life on campus. For instance, the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis has hired wellness counselors to provide holistic wellness services for business school students. Similarly, Columbia University in New York has launched the Well-Being initiative, which lets students know that “your well-being outside of the classroom is just as important as your academic success.”

Priority No. 3: The Whole Person Mindset

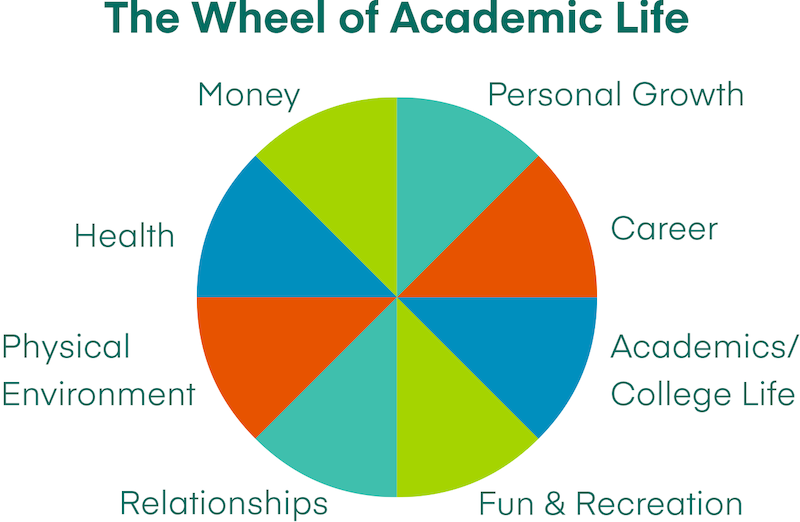

The whole-person mindset views academic performance as just one dimension of overall performance. Many interrelated dimensions are important as well, as illustrated by the Wheel of Academic Life below.

Notice that the wheel gives weight to the concept of work/life balance, which has been found to be a predictor of college student mental health, particularly for students juggling multiple priorities. The wheel is neither exhaustive nor categorical, but its eight dimensions do illustrate some of the facets that contribute to well-being and may even serve as a foundation for curricula development.

The Pedagogy of Well-Being

Over the past four years, I have designed and taught three courses that took a holistic perspective on the leader as a person. All three courses were grounded in science, particularly that of performance psychology and circadian biology, and they were designed to help students develop life skills related to mindfulness, resiliency, and hardiness. The three courses were:

- Stress, Sleep and Performance, created for DePaul University in Chicago. Offered only as a senior seminar to undergraduate business school students as part of their interdisciplinary commerce requirement, the asynchronous course is delivered using a hybrid format.

- Peak Performance, Health, and Wellbeing, created for the Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand. This graduate course for MBAs was delivered in a hybrid format with the possibility of in-person sessions when the pandemic allowed.

- Building a Path to Leadership Excellence, created for the American Association for Physician Leadership, headquartered in Tampa, Florida. This executive-level course is required by the association for students seeking to earn the Certified Physician Executive designation or gain admission to programs at one of its partner schools, such as the University of Massachusetts.

While I built the courses around the three priorities discussed above, I also followed the human-centered design approach. María del Carmen Salazar defines humanizing pedagogy as teaching that seeks to understand that “humans are motivated by a need to reason and engage in the process of becoming.” Human-centered pedagogy also relies on design thinking pedagogical techniques, which take a human-centered problem-solving approach aimed at enhancing creativity and innovation.

Everyone on campus—from the professor to the undergraduate student to the manager in an executive education course—is a whole person and must be treated as such.

Furthermore, a human-centered approach has a core of empathy, which IDEO defines as a deep understanding of those we seek to benefit. The approach also can be considered a pedagogy of care, which Heather Robinson, Maha Al-Freih, and Whitney Kilgore describe as “an effort to understand the role of emotions, specifically the feeling of caring and being cared for.”

I found that a human-centric approach to teaching was particularly important when these courses were taught during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the prevalence of physical and mental health challenges confronting students.

Universal Concepts

As I reflect upon designing and delivering these three courses, I’m struck by the realization of how different the students were. They ranged in age from 18 to 60 years old. In terms of prior educational background, some were college seniors, while others had earned multiple doctorate degrees. Some had zero work experience, while others had been in the workforce for more than 40 years. Among my students were those who had never been married and those who had been married more than once.

Naturally, the framing, packaging, and presentation of the courses varied widely to meet the unique needs and wants of the three student groups. But I used the same underlying pedagogical principles as well as the same knowledge, tools, techniques, and resources. This shows how universal the concepts of mental wellness really are.

Business school leaders must recognize that everyone on campus—from the professor to the undergraduate student to the manager in an executive education course—is a whole person and must be treated as such. One way to act on this recognition is to offer credit-based courses that equip participants with the knowledge and tools to succeed both in school and after graduation. We should prepare our students not just to perform, but also to thrive.